Abstract

Tree restoration is an effective way to store atmospheric carbon and mitigate climate change. However, large-scale tree-cover expansion has long been known to increase evaporation, leading to reduced local water availability and streamflow. More recent studies suggest that increased precipitation, through enhanced atmospheric moisture recycling, can offset this effect. Here we calculate how 900 million hectares of global tree restoration would impact evaporation and precipitation using an ensemble of data-driven Budyko models and the UTrack moisture recycling dataset. We show that the combined effects of directly enhanced evaporation and indirectly enhanced precipitation create complex patterns of shifting water availability. Large-scale tree-cover expansion can increase water availability by up to 6% in some regions, while decreasing it by up to 38% in others. There is a divergent impact on large river basins: some rivers could lose 6% of their streamflow due to enhanced evaporation, while for other rivers, the greater evaporation is counterbalanced by more moisture recycling. Several so-called hot spots for forest restoration could lose water, including regions that are already facing water scarcity today. Tree restoration significantly shifts terrestrial water fluxes, and we emphasize that future tree-restoration strategies should consider these hydrological effects.

Main

In June 2021, the United Nations declared the Decade on Ecosystem Restoration to prevent, halt and reverse the degradation of ecosystems worldwide. Large-scale tree restoration is key in climate change mitigation and for enhancing and protecting biodiversity and ecosystem services1. Under the current climate conditions, it is estimated that an additional 900 million hectares of tree cover could exist on Earth’s surface2 without encroaching on agriculture and urban areas. During the past decade, numerous global and regional initiatives were initiated to increase tree cover, and this will play an important role in shaping global land use over the next decades. Despite these ongoing initiatives and the claims that ecosystem restoration is beneficial to all of the Sustainable Development Goals3, the impact of tree planting on the water cycle and water availability is still poorly understood4,5. As a result, potential impacts of ecosystem restoration on ensuring water availability both downstream and downwind are often overlooked.

Tree-cover expansion impacts water availability locally through its effects on the radiation balance, infiltration and soil water storage, evaporation, streamflow and precipitation6. Traditionally, local impacts of forest cover on streamflow have been investigated mainly using a so-called paired catchment approach. These studies compare two nearby headwater catchments with similar characteristics over a prolonged period, during which one of the catchments underwent land-cover change while the other did not undergo change. These observational studies have, virtually without exception, concluded that tree planting increases annual evaporation and decreases streamflow7,8,9,10,11,12. This high evaporation is attributed to the deeper roots of trees (facilitating access to water during dry periods), higher leaf area index (increasing the precipitation interception and canopy conductance), lower snow-free albedo (increasing the energy available for evaporation) and higher aerodynamic roughness (facilitating turbulent exchange) compared with the other vegetation types9. Higher evaporation has been reported across different climate zones and tree species, but the magnitude of evaporation differs with climate, tree species and tree age7,8. From these studies, it was predicted that large-scale tree restoration will decrease annual mean water availability and streamflow locally9,13,14,15.

In contrast to these small-scale river-basin studies, more recent, large-scale research suggests that the impacts of tree restoration on streamflow are more complex4,6,16,17,18,19. Through atmospheric feedbacks and transport, the increased evaporation from restored trees will partly recycle back to the terrestrial surface (via so-called evaporation or moisture recycling) and thereby potentially increase downwind rainfall and water availability. Such effects of tree-cover change can reach far beyond the river basin or even continental level: tree-cover change in the Amazon forest could impact precipitation in Canada, Northern Europe and all the way into Eastern Asia20. A host of regional and global-scale research has integrated the effects of evaporation recycling in land-cover change studies4,19,21,22. These studies have shown that evaporation recycling has a major influence on the water availability and that evaporation recycling should be considered in future land-cover change studies.

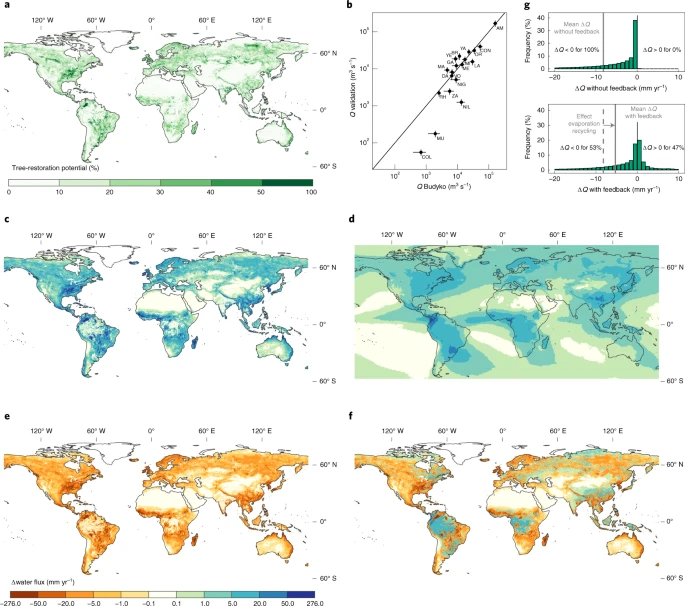

No study has quantified the effects of large-scale global tree restoration on water availability by accounting for both the local, direct effect of increased evaporation and the large-scale, indirect effect of evaporation recycling. The recently published datasets of the ‘global tree-restoration potential’2 and evaporation recycling23 open up an emerging opportunity for such analyses. In our idealized study, we calculate how large-scale tree restoration (defined as increasing tree cover in any region, independent of the land-use history) influences water availability (defined as precipitation water that is not lost through evaporation, the total water available for consumption, on a yearly basis) and streamflow (the amount of water flowing in a stream; in this study, the accumulation of the as-defined water availability on the river-basin scale). More precisely, we calculate how a recent estimate of the global tree-restoration potential2 (Fig. 1a) would impact the fluxes of evaporation, precipitation and streamflow. The global tree-restoration potential dataset highlights where more trees could naturally grow without encroaching on agricultural and urban land. To determine how tree-restoration impacts the long-term partitioning of precipitation between evaporation and streamflow, we use an ensemble of six data-driven Budyko models available in the literature. These six models all include a vegetation parameter that was calibrated separately for forest and non-forest conditions at a 1 km spatial resolution11,24,25,26,27 (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Extended Data Table 1 and 2). We validated the multimodel streamflow under current climate and forest-cover conditions against large river-basin run-off (Fig. 1b). We found good agreement over orders of magnitude, except for the Murray–Darling and Colorado basins, where water extraction probably causes the models to overestimate observed run-off. In addition to the Budyko models, we use the recent UTrack dataset of global evaporation recycling23,28 to calculate where, and to what extent, the increased evaporation could increase (downwind) precipitation. This dataset is created using a state-of-the-art Lagrangian moisture-tracking model29 and presents the monthly climatological mean evaporation recycling (Extended Data Fig. 2). We assume that tree restoration would intensify the current evaporation-recycling patterns as presented in the UTrack dataset. This approach focuses on the regional distribution of evaporated water but does not consider the effect that land-cover change has on local precipitation or atmospheric circulation and recycling patterns. These assumptions are further addressed in the discussion.

Fig. 1: Impacts of forest restoration on water fluxes and water availability.

Fig. 1: Impacts of forest restoration on water fluxes and water availability.

a, The tree-restoration potential2: the percentage area of each pixel that is suitable for tree restoration. b, Model ensemble mean versus observed streamflow (Q) measurements30 for 19 validated river basins. The error bars for Q Budyko indicate the standard deviation over the six Budyko models. The error bars for Q validation indicate a 20% error. The river basins are Amazon (AM), Brahmaputra (BR), Colorado (COL), Congo (CON), Danube (DA), Ganges (GA), La Plata (LA), Mackenzie (MA), Mekong (ME), Mississippi (MI), Murray–Darling (MU), Niger (NIG), Nile (NIL), Orinoco (OR), Rhine (RH), Volga (VO), Yangtze (YA), Yenisei (YE) and Zambezi (ZA). c–f, The absolute annual change in water fluxes after tree restoration: change in evaporation (c), precipitation (d), water availability without evaporation recycling (e) and water availability with evaporation recycling (f). Note that e is the inverse of c: without the feedback of evaporation recycling, the local increase in evaporation equals the local decrease in water availability. g, The histogram shows the distribution of the global changes in water availability without and with evaporation recycling; 89% (without recycling) and 91% (with recycling) of the data fall within the displayed range of –20 mm yr–1 to +10 mm yr–1. All maps display the 0.1° mean values, except for c, which displays the 0.5° mean value.

READ THE FULL ARTICLE HERE

[Source - https://www.nature.com/articles/s41561-022-00935-0#Fig1]